Wind Turbine Blade Defects Interview

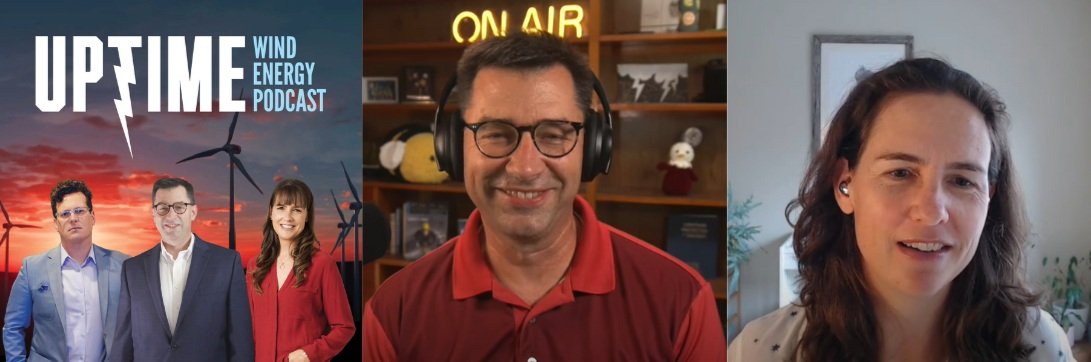

Pardalote founder and director Rosemary Barnes spoke about wind turbine blade defects with Allen Hall on the Uptime Wind Energy Podcast. You can listen at the following links or read the transcript below.

Recorded Fri, Aug 11, 2023

Allen Hall 00:06

I'm Allen Hall host of the uptime wind energy podcast. Our guest today is Rosemary Barnes, founder and CEO of Pardalote consulting. Pardalote is based in Canberra, Australia. And as we all know, Australia is a leader in renewable energy. Pardalote Consulting provides consulting services to wind developers, asset owners and inventors and part of that specializes in technical due diligence, technical assessments and patent evaluation. They have a deep understanding of the clean energy industry and are able to provide clients with accurate and unbiased information. Rosemary is also creative force and host of the wildly popular YouTube channel Engineering with Rosie and she is co-host of the world famous Uptime Wind Energy podcast. Rosemary, welcome to the program.

Rosemary Barnes 00:51

Thank you what a great intro, your best ever.

Allen Hall 00:54

Well Rosemary, we wanted to have you on the podcast because we've never highlighted your consulting business, which is extremely popular in Australia and around the world. Because you are one of the world's blade experts. Do you want to describe what Pardalote does?

Rosemary Barnes 01:15

We work with all kinds of energy transition technologies, not just wind. But I guess today we might as well focus on the wind energy part. We cover all aspects of the technology development lifecycle. So that goes right from conceptual design all the way through to implementation and claims assessments.

Allen Hall 01:35

So Rosemary, your background is in structural engineering, most particularly composite engineering, for blades.

Rosemary Barnes 01:43

Yes. I did all of my degrees in Australia, and I did one year of my undergraduate degree in the US at UC Davis. At the time I had this idea that I wanted to be an aerospace engineer. And UC Davis is a really good aero school. So I went there and completed all of the core aerospace subjects in one year, which was a lot to do all at once, but also really fun. And I learned in the process, that I didn't really want to be an aerospace engineer. Mostly because I'm not so driven to work in defense, which is where most of the work is. But I'm lucky enough that coincidentally, all of the same science and analysis that you use for aeroplanes and spacecraft is very closely related to wind energy. So after six years working in various renewable energy technologies I went back to university and did a PhD. It was a structural design project on composite material structures, specifically related to wind turbines. New ways to design wind turbine blades and other complex composite structures. And then I handed that thesis in one day, and literally the next day, I was on a plane to Denmark to go meet the team of a wind turbine manufacturing company I had a job offer with and I ended up accepting that and living in Denmark for five years.

Allen Hall 03:01

You were working with LM wind power, which obviously is a huge company in terms of blade production, and has some of the most advanced blades on the planet. So you got to be in the factory for a number of years. And I consider that to be a huge advantage if you're an engineer, because you can understand how the blades are made and designed. So when you see problems out in the field, you can get a basic understanding of probably what happened.

Rosemary Barnes 03:25

Yeah, exactly. It's incredibly hard work to work in a factory, and I have always massively respected those engineers that work full time in a factory. I would go for a month, two months, three months, maybe, when I was taking a new product into prototyping or into serial production. But the schedules are intense. Because, you know, those factories are like a finely tuned machine to push blades out. And you know, usually every 24 hours on the dot, one comes on comes off. And so it's almost like choreographed, like a dance ensemble would be in terms of every part happens just right to make sure that the flow of blades off the line doesn't stop.

Rosemary Barnes 04:09

So it's really good to have that experience to see the environment that these are made in. It's one thing to design a blade on a computer. It looks like a tiny little stick that you can you can move around on your computer screen, something nice and small. And then you go to the factory and see what a 70, 80 meter blade actually looks like, and the reality of how they're made. It's mostly, it's a pretty manual process. There's some automated assistance, but in general, it's very manual. And the kinds of engineering design and the controls that you need to make sure that you get a consistent high quality product out of a manual process – you have to experience it to understand it, I think.

I worked on the other side as well, when I was working with blade heating systems to keep blades, ice-free in cold climates. I would work on new product integration in the factory, but then also installing it in the field, commissioning, validating, climbing towers to make sure that the systems still look the way they were supposed to after a few months, after the first season. And then also working with claims if there was a problem down the line, to figure out why the problem happened and how to repair it. Because when something is inside a wind turbine blade, it's very hard to do anything to it. If it's in the very root of the blade, you can climb up and poke around and fix it, it's still going to be expensive and painful if you have to do that on a whole fleet. But if it's further in the blade than there's space to climb into, then, you know, you’ve got a problem there. And then you’ve got to get really creative with your repair solutions.

Allen Hall 06:04

In your experience in the factory, in the field, climbing towers, I think that's unique in a lot of engineering, usually engineers can get pigeonholed. And a lot of people like that, actually, they prefer that. But the road you took was a little bit different. You're doing a lot of different aspects and learning the business and understanding how the business work, but also understanding how engineering works.

Rosemary Barnes 06:27

Yeah, so one of the reasons why I took that that job being the system owner for the blade heating systems, it's because it really did touch on a lot of different aspects of not just the wind turbine blade, but the whole wind turbine, and then the whole wind industry. Because it's not just something that's affecting the blade structure. It also you know, has a control system that needs to talk to the turbine controller. And then it's also an important part of the sales process. If a developer wants to install a wind farm in northern Sweden for example, then the de-icing system is going to be one of the most important technologies that they're going to be using to differentiate the manufacturers. So yeah, I was involved all through that whole lifecycle, right up to claims as well.

Allen Hall 07:20

So you went back to Australia, sort of just as COVID was starting and created your consulting business?

Rosemary Barnes 07:27

Yeah, just after.

Allen Hall 07:29

Just after? Okay.

Rosemary Barnes 07:30

Yeah, it was because of the pandemic, that we went back. It was just, Australia was a very difficult place to, you know, it was great to be inside Australia. But if you had family there, and you were outside Australia, it was hard.

Allen Hall 07:43

But that opened up some doors. So in terms of the consulting business, because you came back loaded with skills, and you had an intimate knowledge of blades.

Rosemary Barnes 07:52

I've realized that actually, the timing was perfect. And I think Australia is actually the most exciting energy transition at the moment, when you see how fast we're putting in variable renewable sources. So wind and solar, it's growing faster than anywhere else. And we're getting up to a really significant share of our electricity grid that is from variable renewables. There's plenty of countries that have 100%, or close to 100% renewables, but it's usually a lot of hydro, and geothermal, which are a lot easier to manage in a kind of traditional way, because they more closely represent big thermal, fossil fuel power plants. But we're doing it with wind and solar, which you can't just turn on and off whenever you want to, and you can't predict it along a long way out. And so the challenges in dealing with a high proportion of variable renewables, it's Australia that's going to be solving those challenges first. And, to a certain extent, we already are doing that. And so I find that a really, really exciting thing to be part of.

Back in 2010 [when I made the decision that I wanted to leave Australia to work in the wind industry in Europe], it didn't feel like we were doing much in renewables. But the period since then a lot of wind energy has been rolled out. And now we're definitely at the point where there are defects in the field. Some of my clients in Australia that I work with on wind farms, I help them with finding new technologies. So that's early in their development cycle. But the big bulk of the work that I do is when there are problems. When they've got blade defects, and they're not really feeling like the manufacturer is taking them seriously or they don't quite feel sure that that the right thing is happening. That's when I step in to help. So in that sense, it's kind of perfect timing for that as well, because, you know, there's not a lot of people like me in Australia that have that experience in factories and climbing towers. I've worked with engineers from nearly all of the OEMs. And so I jokingly say I speak the language of the Danish wind engineer. It's true, both literally and metaphorically. So I think that the timing is great for someone like me to move back to Australia,

Allen Hall 10:14

Australia is booming in the wind industry and solar energy and all kinds of renewables and your expertise in that area is got to be a huge advantage to Australia in general. And I remember early on talking with you, you seem to be involved in a lot of initial looks at new sites and what kind of turbines to put where it seemed like, you're getting a lot of questions about that. And as the industry has grown, obviously, you're getting more and more into like the problem child wind turbines out there and getting them back in service. What are some of the big constraints you have right now in Australia, and on the service side, and the maintenance side where you get brought in? Like, what does that typical client look like? What are they asking you to do?

Rosemary Barnes 10:57

So the most common category is blade defects. Usually, at first it's one or two or three defects, and the wind farm owner is starting to suspect that it might be part of a wider trend, and the manufacturer is assuring them that it's not, they're just unlucky. So then I'll step in to help with that process. Usually first of all, the important thing is to just get the OEM to start taking them seriously and to engage. And I think that just having me there helps send a message. I'm known in the industry, so people know, okay, we're not going to be able to fob them off anymore. Because I’m always going to be asking the hard questions. And I know how it's normally done, you know. I've been on the other side of the table for all of the kinds of work that I do like that. So I know what the manufacturer can do. And I know when they're taking it seriously or when they're not. So usually the first thing to do is ask to see their root cause analysis. When there's more than a couple of defects that might be the start of a pattern, then a manufacturer is going to get a team together and say, what's caused this and brainstorm a whole bunch of ideas, and then try and figure out what the reason is. And they might do some more tests to figure out which ideas are plausible or not. So the first thing to do is to get involved in in that process to have a look at their root cause analysis and to ask them: Did you consider this? Did you consider that? Or maybe: you've said that this is your most likely root cause. But that doesn't seem to match with this other fact that you told us earlier on. I just really get in there and question everything. And that usually helps push things along.

Rosemary Barnes 12:42

One of the big issues that I see is in Australia, it's really popular to have service agreements with an OEM. So you know, you buy the turbine, and at the same time you buy a service agreement from the manufacturer for often the whole life of the wind farm, or at least for quite a number of years. And Australian developers like this, because they think that there isn't a lot of wind turbine expertise in Australia. There's a lot of development and construction project expertise, we're very good at that. But when it comes to the actual technologies in a wind farm, operating a wind farm, building a wind turbine, and all its components and maintaining it, there isn't that expertise there. And the developers know they don't have it. And so they feel it makes sense, that the OEM is going to do the best job of this. And then any issues that they have, they'll be first in the queue to have them solved because they're their own client. That sounds good. And it usually is really good until the point where they have a problem. Which they might not even know until there's enough downtime, that it starts to show up in, you know, a monthly report of generation or, you know, on the balance sheet. That might be the first that they hear that there's actually a problem. And then they might start to realize that there isn't much in the contract about their rights to documentation, their rights to request actions to be taken, often they're not even allowed to climb their own turbine, they're not allowed to bring somebody in. One of the things that I'm doing is to suggest monitoring intervals and methods to monitor a situation. You might want to put a sensor in a blade to monitor for an issue and the manufacturer with a service agreement says no, you can't do that. And so that can be really restrictive.

Allen Hall 14:39

Yeah. And Pardalote should be brought in early in the process to get these ground rules in place before the farm is built. Because you're right. I think a lot of operators don't think about the consequences if something goes wrong. What is the OEM going to do for you, you kind of assume they got your best interests at heart, not always the case. Obviously, Australia is not a place where blades are made. So all the blades that come in country are coming from usually far outside. How much of the blade issues that are happening in Australia are just due to shipping and trucking and all the transport?

Rosemary Barnes 15:14

I think a normal amount, which is probably higher than most people would assume. When I started working for LM Wind Power, I was shocked at how often my blades got damaged in transport. I also think I was unlucky with my projects. When I was working on a new technology, you usually make one set of prototype blades, right? So you've got three, you don't usually make a spare occasionally you might, but you know, those three blades become very precious. And everything happened to my blades. There was fire, there was forklifts driven into them. One, no, two separate times someone slid out on an icy road and tipped the blade into a ditch. A mold fell off a ship.

Allen Hall 15:57

Wow.

Rosemary Barnes 15:58

Yeah, like it's just it's crazy. The amount of the amount of stuff that you know, there might have been a dozen prototype blades that I worked on in my career, and something happened to just about every single one of them. So yeah, I mean, it happens. Transport damage happens. It's rare that it's that bad, though. In fact, maybe I've seen one that I've worked on [in Australia]. But in general, it's really well defined there. People know how to repair them. And there's no, there's no issue, you know, they just, it's just something that happens. And so there's a system in place, and you just fix it and put them up and no one ever thinks about it again. So yeah, that's not such a big, big problem.

Allen Hall 16:36

So the blade issues that are happening tend to be more in the in the quality inspection, manufacturing side of the production rather than anywhere else. And that tends to be true in a lot of cases. So Australia is so far removed from actually the factories. There's not a lot of news that travels. In Europe, word spreads quickly if there's a blade defect, but it may not travel all the way to Australia. How do Australian operators try to keep up with all the technology all the things that are happening? We've been seeing issues with Siemens Gamesa, we've seen issues with TPI? Can you help your customers understand, like, what's likely to be going on in those factories, when Siemens complains about wrinkles, for example, in the blade molds, and TPIs complained about that recently, too, on the quality side, I'm assuming Australian operators really don't have an idea what that really means. Can you translate that for them and help them understand this is the risk, this is what you need to be watching for?

Rosemary Barnes 17:32

I definitely can. And it's something that I really want to do a lot more of. I've started reaching out proactively to, to developers, and yeah, asset owners about issues that they might face, because I think it's not something that Australians are used to thinking about. One thing I'm really hoping to get in at an early stage is the offshore industry that hasn't quite reached the level that needs my involvement yet, but soon, they are going to be having conversations with manufacturers about which turbines they're going to get and which technologies are going to be in those turbines. And, you know, the way that their sales process works and their technology development process works is often sales commitments are made before technologies are actually fully developed. And definitely before they are, you know, fully matured and validated. And again, this is a topic that I worked on, when I was at LM Wind Power, when they would have sold a turbine that has a system in it, that is currently an idea in my head, and I've just had a conversation with a couple of business development or sales people. And then potential customers need to feel confident that this is going to do what I say it's going to do. And especially their banks are very interested to know that it's going to do what what we're promising. And so there's a whole process where you get together the customer and the manufacturer, and you talk about how this technology is going to be developed, what technical milestones you're going to hit and when and what kinds of tests that you're going to do. So we know a lot of customers wouldn't realize that if you're going to place a big order for a new technology, if you're going to be one of the first customers for a new technology that it is totally reasonable for you to ask them to do certain tests to de risk it. Because I mean, it's great to be cutting edge and be the first person with a shiny new technology, but you don't actually want to be a guinea pig. So you can get someone like me at Pardalote in to go in and then question what their plans are and to make sure that you add in the right tests at the right time so that you have something that might be new, yes, but you're going to be confident that it's going to work.

Allen Hall 19:46

Yeah, let's go down that pathway just for a moment because I want to understand on the structural side blade structural type certification. We're getting a type certificate for a blade on a particular new blade. So if I'm in Australia, and you're getting offered a lot of new products in Australia because the marketplace is huge right? And there's a lot of emphasis on bigger turbines, most likely an operator in Australia is going to be offered a brand new turbine, a brand new blade design, when you're involved in that and brought in early on to help that operator kind of walk that pathway. When you're working with an OEM, are there things that they should be doing beyond that sort of type certification structural test on a new blade designed to verify: Yes, is going to be working in Australia for the next 25 years?

Rosemary Barnes 20:35

Yeah, there are. And it depends on how unusual the technology is. So if it's just a totally standard blade that has nothing particularly special on it, then I would trust the standard certification process would be good enough. And there'll be no need to do anything else. But if you think about one blade that I worked on, when I was at LM, and that we have a lot of in Australia is the Cypress platform. They had those split blades: the blades come in two pieces. And so I was working on that, while I was still in Denmark. And then we had a team of early customers come over and LM demonstrated how that is going to work. And we answered questions about, what happens if X, what happens if Y happens. And the results of that meet and greet Show and Tell kind of thing is that the development team gets ideas, and also makes promises to reassure their customers, and they do actually shape the development process a bit. It's not totally sealed off where the customer just gets what they're given. When you get involved early, and in that early process, you do have the ability to request extra tests too. You know, say, Don't you think that this problem is likely to happen? And then the engineering team goes off and tests for that issue. And finds, Yeah, okay, our customer is right there, there is a risk that this happens. And so they tweak the design a bit, so it doesn't happen. So yeah, when it works well like that you get a much more reliable product.

Allen Hall 22:21

Well, let me ask about another problem area, which is worldwide, but I think Australia is unique in this. And your experience is unique. Lightning. And you as a structural engineer, were around lightning testing and lightning design because you're designing blade de-icing systems, which tend to be electrical systems. And lightning is a big concern around that. So you've had some exposure to the lightning testing world and sort of what happens in the field. In Australia, the lightning is particularly odd, I think, at times, and it would seem like the lightning damage you would see on blades are maybe a little bit unique, versus what you may see in Iowa, United States. And your expertise, there is going to be super helpful if I'm an operator in Australia, and I'm taking some lightning strikes, I would want to have your eyes on it from a structural side to determine Am I in trouble? Do I need to do anything about it?

Rosemary Barnes 23:16

In a perfect world, a wind turbine has a lightning protection system in it, it gets struck by lightning and the lightning goes through the lightning cable and into the ground and everything's fine. The blade is still perfect afterwards. So you wouldn't need to repair in a perfect world. But every now and then a strike is a bit bigger or it hits somewhere that you weren't expecting. Because lightning strikes are statistical. So if you have one damaged wind turbine blade, you can't say this is a defective lightning protection system. Because, it might have been a bigger strike than it was designed to take. It might have struck in a place that just was just one of those things, you were the freak occurrence that it hit somewhere that is one in a million chance. But when you get two like that, like okay, so it's a bit harder to believe that this is two one in a million events we’ve experienced. And then you get three, four or five, at what point do you start to say, Okay, this is actually a problem with the lightning protection system and the manufacturer is responsible for this. You get these interesting fights between the asset owner, the insurance company and the manufacturer, these kind of three way fights where everyone's trying to push off responsibility on to someone else. And if there are a small number of blades involved, too small to do statistical analysis on then it is usually the asset owner that just ends up having to repair that. The really interesting issues in lightning are when you to try to establish that a system is not designed correctly. And I think when you look across the whole planet's wind turbines at the moment, you do get enough numbers to see something is different now. There's more damage than there used to be. I made a recent video on my YouTube channel on how the whole process works with design and testing and certification, and then how that actually fares in the field. And you helped me with that, Allen, so you're, you're aware of what we did there. It's because blades are getting longer, and they've got carbon fiber. Those are the main two reasons why things are different now. And then, yeah, lightning also varies from area to area. So maybe until recently, we didn't have that many wind turbines in Australia that it was obvious that that things were maybe not quite the same here. But that's all still playing out. And yeah, those are the really interesting issues when you're looking at the design itself, rather than individual damages.

Allen Hall 26:09

Well, that's why you're so useful in Australia, with the Cypress blade in particular. So let's just talk Cypress, just for a brief moment. The Cypress, because it's a two piece blade has a unique lightning protection system, unlike any other blade that I've ever seen. And you being up close to that. And that blade being used a lot in Australia has got to be a huge advantage in terms of knowledge base. So if anybody has a GE turbine that's having some issues. Well, Rosemary is your person to call because she probably understands what happened on the inside what why it's designed the way that it is. And you're right. I mean, as much engineering as a company can throw at a problem when you're delivering products worldwide that do affect the atmosphere, and they do affect how lightning strikes. They're going to react differently in different countries. And it's good to have you and Australia kind of following up on that and being a resource for Australia. That's hugely important.

Allen Hall 27:03

Rosemary, it's been great to have you on the podcast to talk about Pardalote Consulting. How do people reach out to you and get a hold of Pardalote Consulting?

Rosemary Barnes 27:12

Well, you can head to the website, which is pardaloteconsulting.com. And I actually just the other day, put up on the blog page, an article about lightning. So if you are worried about lightning, then you can go check that out. And I am gradually adding in technical articles about all aspects of wind and other other things in their energy transition. You can also find me on LinkedIn. Pardalote Consulting is on LinkedIn as well. But yeah, Rosemary Barnes on LinkedIn, and on Twitter, it's @engwithrosie, which is linked to my YouTube channel Engineering with Rosie. Yeah, so that's probably the biggest, biggest resource. There's a lot on wind energy on there. My early videos were were nearly all just based on you know, personal experience and knowledge. So yeah, especially check out the back catalogue if you're interested in wind energy.

Allen Hall 28:15

Rosemary it's been great to have you on as a guest. We have been co-hosting together for so long now. We just figured now's the time we need to have you on as a guest and talk about your consulting business because it's doing great work. So Rosemary, thanks for doing this.

Rosemary Barnes 28:27

Yeah, thanks a lot for having me.